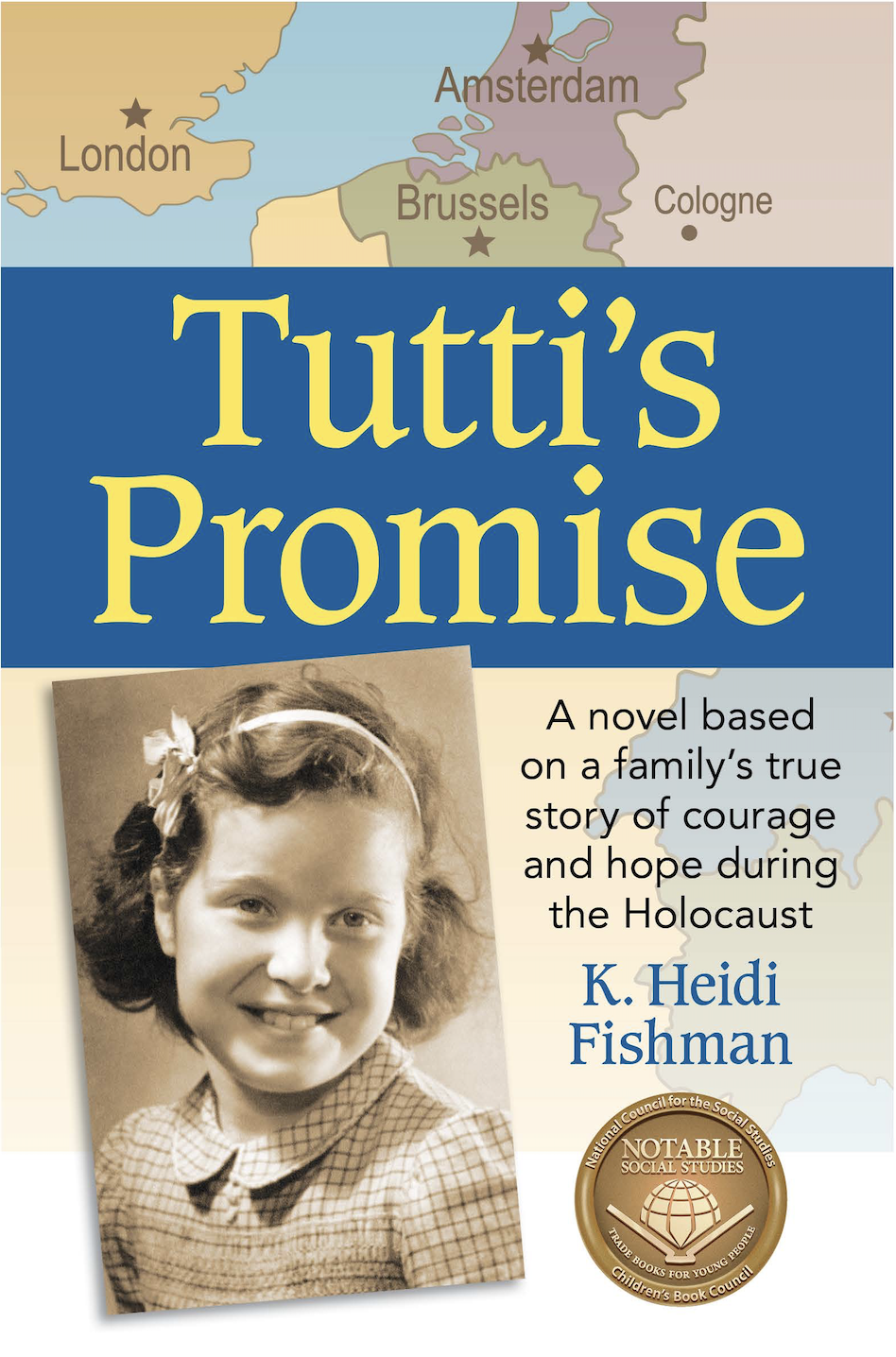

TUTTI’S PROMISE: A novel based on a family’s true story of courage and hope during the Holocaust

By K. Heidi Fishman

For ages 10 and up

A promise kept is like the twinkling stars in the night sky: a constant reminder of something important that makes you who you are.

AWARDS

NATIONAL COUNCIL FOR THE SOCIAL STUDIES & THE CHILDREN’S BOOK COUNCIL:

• A NOTABLE SOCIAL STUDIES TRADE BOOK FOR YOUNG PEOPLE

IBPA BENJAMIN FRANKLIN AWARD:

• SILVER WINNER: BEST NEW VOICE: CHILDREN’S/YA

• SILVER WINNER: YOUNG READER: FICTION (8-12 YEARS)

MOONBEAM CHILDREN’S BOOK AWARDS:

• GOLD MEDAL WINNER FOR PRETEEN FICTION—HISTORICAL/CULTURAL

NAUTILUS BOOK AWARDS

• SILVER WINNER: MIDDLE GRADES FICTION

“Drawing on the author’s family history, Tutti’s Promise is a wonderfully moving and evocative story of love, hope and survival in the very darkest of times. Highly recommended.” —ROGER MOORHOUSE, HISTORIAN AND AUTHOR

"That the family survived to have this powerful, heartening tale told cannot fail to move readers.” —BOOKLIST, ANNE O'MALLEY

The prologue and the first two chapters of Tutti’s Promise are below:

Prologue

Tutti, eighty years old, was sitting outside the principal’s office.

She wasn’t a student, of course, but was a guest at the school. The principal had invited her to talk with the eighth graders about her childhood under the Nazis.

This was not the first school Tutti had visited to tell her story, and so by now, she knew by heart what she wanted to say. The first time she had spoken to a group of children, she had carefully written out her talk on index cards. Now she left the cards at home.

My name is Ruth Lichtenstern Fishman, but everyone calls me Tutti, she always began. I was born on July 17, 1935, in Cologne, Germany.

Two years earlier, Adolph Hitler had come to power, and the Nazis started passing anti-Jewish laws, keeping Jews out of certain jobs and schools and burning books by Jewish authors. Then in September 1935, the Nazis told us that we were no longer German citizens.

My father and grandfather worked for a metals-trading company called Oxyde. The owner was Jewish, and he decided to move his business to the Netherlands. So in 1936, my family moved there, too. But four years later, we found out that we hadn’t moved far enough away from danger . . .

Tutti with her parents, Margret and Heinz (1935) Tutti Lichtenstern Fishman, age 80

Tutti and Robbie Lichtenstern (1940)

1

Invasion

May 10, 1940

Tutti awoke with a start. Robbie was crying. She heard strange sounds outside—big booms. Juffie, the nanny, was rocking two-year-old Robbie and trying to get him back to sleep. Tutti, nearly five years old, climbed out of bed and found Mammi and Pappi peering out the window in their pajamas.

“Mammi, what is that noise?” asked Tutti.

“Margret, look who’s here,” Heinz said. “Did all that commotion outside wake you, Tutti?”

Yes, Pappi,” she answered, rubbing her eyes.

Mammi quickly picked her up. “Whatever it is, it’s far away,” she said. “Don’t be scared.”

Mammi brought Tutti back to the nursery and tucked her into bed. She collected Robbie from Juffie and patted his back until he settled down. Then she gently laid him in his bed and pulled the soft blanket up to his shoulders. She kissed Tutti on the forehead, smoothed her red curls, and picked her doll up off the floor, placing it next to her. “Gute Nacht,” she whispered. “Juffie will stay right here, so there’s no need to be frightened. I’ll let you know what all of this is about in the morning.”

But when the sun came up, with the buzz of airplane motors in the distance, Tutti became focused on something new. She wondered why the radio was on so early and why Pappi scowled and gripped the sides of his armchair as he listened to it. “Mammi, why is the radio on? What is Pappi listening to?”

“Shh, Tutti,” said Mammi. “Pappi needs to hear the news.”

“German troops have crossed the Dutch frontier and are in contact with our border forces. There have been landing attempts by enemy aircraft and paratroopers,” squawked the radio.

“Pappi, why is the radio so loud?” Tutti asked.

“Shh, Tutti,” Pappi insisted.

“Heinz, please turn down the radio,” said Mammi, lifting her eyebrows slightly. “The children are awake now,” she said, scooting them into the kitchen for breakfast.

“The bridges over the Meuse and IJssel have been destroyed.” Robbie began to cry. Mammi picked him up and walked to the window.

“At least seventy German planes were shot down, with Germans using Dutch prisoners as cover.”

Tutti ran back to the living room. “Pappi, can we turn on some music? Robbie doesn’t like this man’s voice and neither do I.”

“Um Gottes Willen!” Pappi bellowed. “Margret, please keep the children with you. This news is important.” He got up to adjust the dial and remained standing beside the radio, scowling.

Mammi took Tutti by the hand and led her away, but it was impossible not to hear what the announcer was saying.

“Paratroopers have landed at strategic points near Rotterdam, The Hague, Amsterdam, and other large cities . . .”

All three sat at the table, but Mammi stood up a minute later. “Tutti, please help Robbie with his breakfast. Juffie’s not here. She left to make sure her sister is all right. I’ll be right back.” Mammi went into the living room and turned down the blaring radio, but she didn’t return to the table right away.

“And now I will read Queen Wilhelmina’s speech to the people of the Netherlands,” Tutti heard the announcer say. She listened carefully, but he said a lot of words she didn’t understand:

“To my people! After our country has scrupulously maintained neutrality, last night the German troops suddenly attacked our territory without the slightest warning . . . . I herewith protest against this unprecedented violation of good faith and condemn the attack as a flagrant violation of international law and decency. My government and I will now do our duty. You must do yours with the utmost watchfulness and with inner calmness and devotion . . .”

Heinz turned off the radio and stood to give Margret a hug. “The phones aren’t working. We have to check on our parents,” he said.

“You’re right. They must be worried about us, too.”

“I’ll go to my parents’ apartment first and then Flo and Louis’s. It won’t take me long. I’ll be back in an hour or two,” Heinz said, squeezing his wife’s hand.

When Mammi came back into the kitchen, Tutti saw she had tears in her eyes. She hadn’t really understood what the announcer was saying, but she knew it wasn’t good news.

gute Nacht (goo• tuh nahkht): good night (German)

Juffie (yoof• ee; oo, as in the oo in took): A nickname meaning “Missy” (Dutch)

Tutti (too• tee; oo, as in the oo in took): Ruth Lichtenstern’s nickname

um Gottes Willen (oom gawt• ehs vill• uhn): for God’s sake (German)

Tutti about to leave on her date with Margret’s brother, Tutti’s Uncle Bobby

2

A Date with Uncle Bobby

Summer 1940

Within five days of the invasion, the Dutch army surrendered, and the Germans marched into Amsterdam. A small fraction of the population joined the Dutch Nazi Party (NSB), but hundreds of thousands of Netherlanders rebelled through acts of brave resis-tance—going on strike, creating underground newspapers, and hiding Jews. Some engaged in sabotage, such as cutting phone lines, destroying rail lines, and disabling German vehicles.

Those Jews who tried to flee were mostly unsuccessful. The country’s geography and the dangerous Nazi-infested North Sea made escape essentially impossible.

If only the land had had a different topography. If only it had not been devoid of mountains and forests, which would have provided sanctuary and cover. If only the surrounding countries had not already fallen under German control. Then the fate of the Jews in the Netherlands might have been much different than it was.

But Tutti was blissfully unaware of all this . . . and was especially happy one summer day after she turned five . . .

“Come, Tutti. Let’s get you dressed. Your uncle Bobby will be here soon.” Mammi opened the closet and easily slid the hangers across the rod one by one until she found the dress she was looking for. “How about this one?” She pulled out a blue dress with white trim. Tutti had worn it only a couple of times and just loved the way it swished around her legs when she twirled.

“Mammi, where is Uncle Bobby taking me to lunch?” Tutti was already shedding her play clothes.

“The Blauwe Theehuis in the Vondelpark. Do you think you’ll like that?“

“Oh, the Vondelpark!” Tutti jumped up and down. “Can we feed the ducks?”

“I’m sure you can.” Margret smiled at the child’s enthusiasm and felt her heart fill with love. For Tutti, little had changed since Germany’s invasion. But for Margret, there was tremendous concern: How would each new policy affect them? The Nazis had recently ordered Jewish-owned businesses to hang up signs that read “Jewish business.” How would Heinz’s job be affected? And how would she keep her family safe?

Margret held the dress for Tutti to step into and then buttoned up the back. She watched as Tutti spun around and her little dress flared out. How simple things could bring her child such joy! Margret would do whatever it took to make sure that Tutti could enjoy these little pleasures—a new dress and lunch with her handsome young uncle—and not have to worry about the war. She helped Tutti with her socks and shoes and completed the outfit with her new coat. Just as they were buttoning it, there was a knock at the door.

“Uncle Bobby!” Tutti ran to Bobby and threw her body into his open arms. Bobby, dressed in a blue suit and striped tie, his hair smartly parted to the side, lifted a package above his head so Tutti’s embrace wouldn’t crush it. He laughed at her exuberance and returned the hug.

“Is that present for me?” Tutti asked.

“No, sweetheart, this gift is for Robbie. It’s a pony.”

“Oh, he’ll like that. But why can’t I have a present too, Uncle Bobby?” she protested.

“I’m taking you out to lunch. I brought this for your brother since he’s too little to join us. Now which would you rather have, a present or an afternoon out with your favorite uncle?”

Tutti thought it would be nice to have both but understood that it wasn’t something to say out loud. Anyway, she soon forgot all about Robbie’s present because the afternoon was so much fun. She felt like a teenager on a first date.

Her uncle ordered them pancakes with jam. Tutti tried to remember all the manners her parents had taught her. She put her napkin on her lap and didn’t use her fingers to eat her pancake, except once. The hardest rule to remember—because she had so much to tell her uncle—was not to talk with her mouth full!

For dessert, Bobby ordered a whole tray of little cakes—with pink and white and yellow icing, and little candied violets and tiny silver balls. They were so beautiful she could hardly stand to eat them. “Enjoy them now, Tuttchen,” her uncle said, taking a bite of one. “If this war goes on, there won’t be so many nice things to eat.”

When Bobby finished his coffee, they strolled to the pond. Tutti crouched by the water’s edge and watched how the ducklings followed their mother around. “Are you and Aunt Tineke going to have a baby, Uncle Bobby?”

“Someday . . . that’s certainly the hope. Why do you ask, Tutti?”

“Well, because then I could have a cousin to play with,” she said, throwing a handful of crumbs to the ducks. “All of mine live far away. Why did everyone move to England?”

Bobby looked uncomfortable. “Oh, Tutti, people move for lots of reasons.” He threw the last of the crumbs into the water and brushed off his hands, one against the other. “Maybe your mammi can explain it better than I can. But you know what? I’ll see what I can do about having a baby soon—just for you.”

Blauwe Theehuis (blau• uh tay house): Blue Teahouse (Dutch)

Tuttchen (tuhtch• ehn): An endearing nickname for Tutti (German)